Part 1: Introduction

When you think of astronomy, you probably think of optical telescopes - instruments designed to directly see light passing through them. These tools have been the backbone of the field since Galileo, but fall short in one crucial aspect - if a light particle, or photon, is energetic enough, it won’t make it to the surface. Instead, it interacts high in the atmosphere, producing a cascade of many different particles called an “air shower”.

Very high energy photons are a key piece in understanding how the most extreme processes in our universe work - things that happen in environments such as supernovae, merging stars, and black holes. But here on Earth, we can’t see these photons directly!

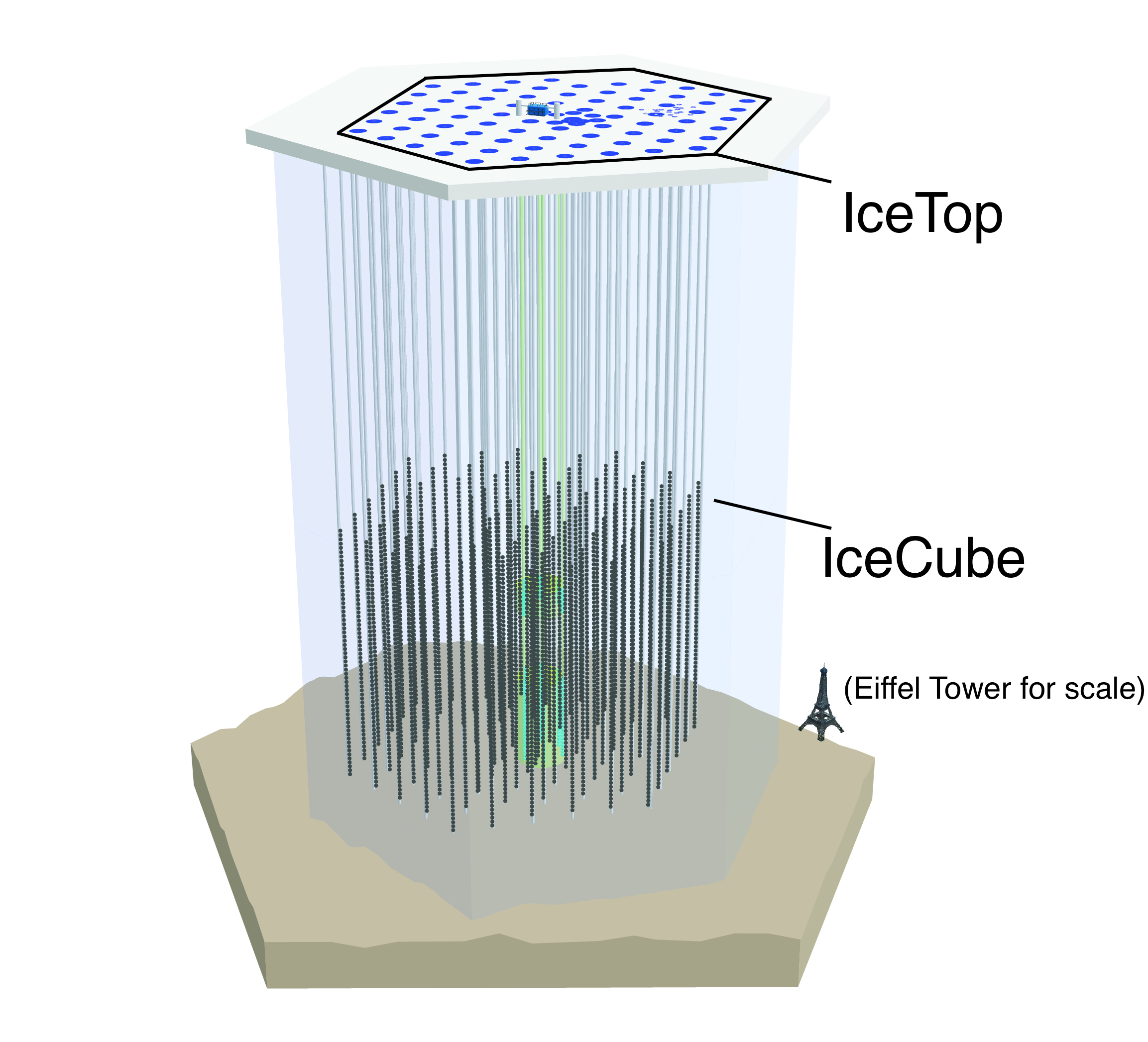

One solution is to build many small detectors, spread over a large area on the ground. This way, each detector sees a small portion of the air shower when it reaches the surface. This is the design concept behind IceTop: the surface component of the IceCube observatory at the South Pole.

A total of 162 detectors spread across a square kilometer on the ice make up IceTop. Combining information from each detector allows us to reconstruct the original direction and energy of the particle that entered the atmosphere. The sheer area covered by these detectors give us access to extremely large air showers, and accordingly very high energy particles.

Problem solved, right?

Well, not exactly. It turns out there are many different types of particles entering our atmosphere all the time. These other particles are nuclei of the elements: protons, helium, iron, etc. As a group we call these particles “cosmic rays”, and they are produced by extremely powerful objects just like photons.

However, unlike photons, cosmic rays have a magnetic charge. This means they are scrambled in outer space by magnetic fields on their way from their source to Earth, making it impossible to determine where they came from. If that wasn’t enough, it turns out there are thousands of these cosmic rays entering our atmosphere for every 1 photon!

Of all the air showers seen by IceTop, those produced by photons are the needles in the proverbial haystack. Extracting these needles is the binary classification problem that has been the crux of my research.

Part 2: Classifying Photons and Cosmic Rays

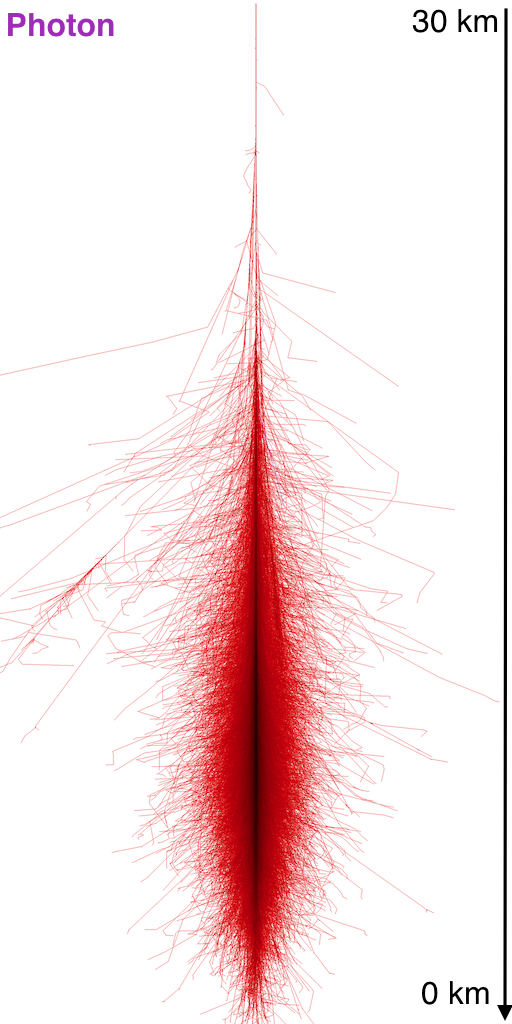

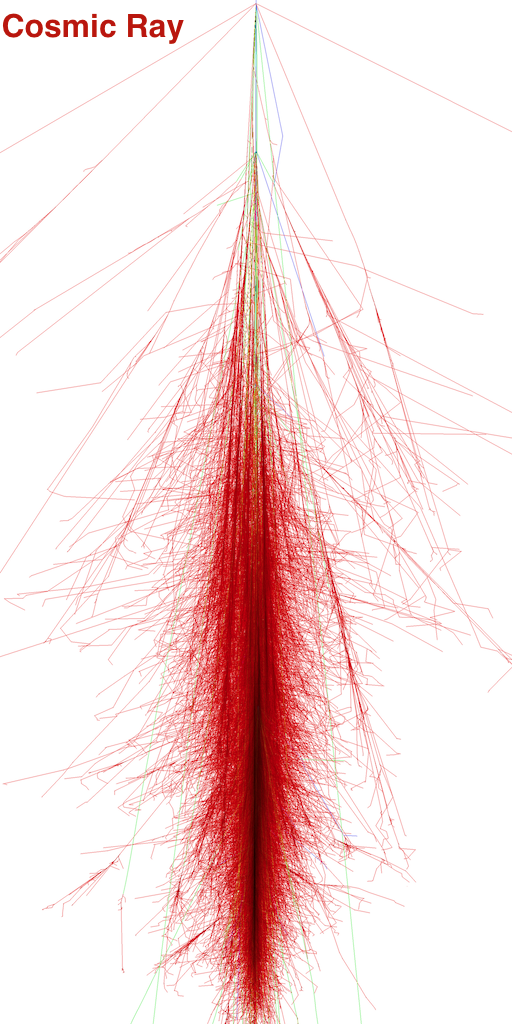

Fortunately, there are some key differences between air showers produced by photons and those made by cosmic rays. Compared to photon air showers, cosmic-ray air showers:

- are less uniform

- develop earlier in the atmosphere

- produce many more muons, a subatomic particle which can travel deep underground

These differences are apparent when seen side by side:

The physical differences in these air showers manifests in the data recorded by the observatory - the job falls to the researchers to engineer features which most effectively conveys this information. My collegue Hershal Pandya and I worked extensively on developing what became two key features discriminating photons and cosmic-rays:

- A ratio of likelihood maps for IceTop stations in charge, time, and distance, conveying information about muon content and shower curvature.

- A cleaned measure of charge recorded by the IceCube detector which conveys very pure information about the amount of muons in the shower.

These features were combined with the reconstructed direction and energy of the air shower, as well as a feature indicating whether the air shower passed through IceCube. In order to maximize the seperation power of these features, I utilized a Random Forest classification model using the open-source software package scikit-learn.